Ellis Island's role in the difficult battle it was for women to gain the right to vote

By the time Ellis Island opened its doors in 1892 welcoming young Annie Moore from Ireland as its first arrival, the fight for women’s suffrage – the right to vote – had been raging for 44 years. The movement began in 1848 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, among other brave women, held the first Women’s Rights Convention in July in the little town of Seneca Falls, New York (home to the Women’s Rights National Historical Park). In the early twentieth century the politics of suffrage reached Ellis Island as prominent suffragists from abroad were detained at Ellis Island due to their political activities. Since 2020 is the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote, this month’s blog explores the role that Ellis Island played in that long struggle.

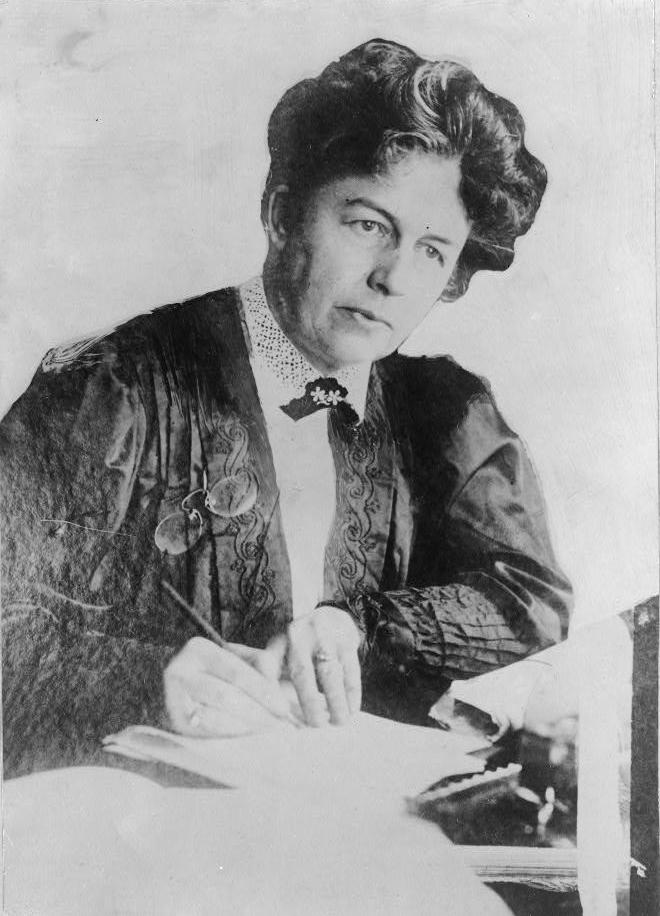

Harriet Stanton Blatch

From its beginnings in Seneca Falls, where the “Declaration of Sentiments,” based on the Declaration of Independence, gaining the right to vote for women in America, as well as other countries, would take more than one generation of women’s time and passion. Surprisingly, one major roadblock in gaining the right to vote wasn’t from men, but from women themselves. For example, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the literary work that provided fuel for the American Civil War, was against women voting. Millions of women felt that voting was outside of their sphere of influence and simply did not want it. Ironically, the 19th century’s most famous female leader – Queen Victoria of England, was against woman’s suffrage.

Mrs. O.H.P. (Alva) Belmont

In the early twentieth century, the second generation of women were fighting for women’s voting rights. Between the upheaval of the Civil War, differing viewpoints on how to agitate for the vote, and the new ideas of the younger generation the movement began to change. Part of that change was due to a British woman – Emmaline Pankhurst. Mrs. Pankhurst began to agitate for civil disobedience in order to gain the attention of a government that was not responding to women’s politer pleas. Her radical ideas spread to the United States after New Jersey native, Alice Paul, spent some time working with her in England. Paul brought similar tactics – parades, picketing, and hunger strikes to American shores.

Naturally, Emmaline Pankhurst was revered by many American women in the suffrage movement and traveled to the United States on more than one occasion to meet with them and make speeches. Her first three visits to America went unnoticed or unchallenged by authorities as she traveled to New York on the Paris in 1893, the Oceanic in 1909, and the Oceanic again in 1911. But as the La Provence steamed towards New York Harbor in October 1913 a frenzy of activity for weeks had been undertaken by those for and against Mrs. Pankhurst’s visit.

An editorial in the New York Times dated September 7, 1913 referred to Pankhurst as the “foremost British anarchist.” The motives of the Women’s Political Union, who were sponsoring Pankhurst’s trip were called into question – “American women who join to welcome her with a feast are lowering themselves.”

Emmeline Pankhurst Being Arrested 1907-1914

A letter from the London office of the Consul General outlined the crimes and misdemeanors for which Mrs. Pankhurst was charged including, inciting violence and property damage and notes that she was charged under Section 10 of the Malicious Damage Act of 1861. The letter goes on to note that there was some disagreement to whether or not she was guilty of what was called, “moral turpitude.” While the letter makes no specific recommendations regarding Pankhurst the inclusion of many negative articles from the London Times sent emphatically in triplicate, gives little doubt to the Consul’s opinion.

This was one of many letters received by immigration officials. Another, written September 16, 1913 by Charles Requa and written on letterhead of the New York Press Club rails not only against Pankhurst, but accuses Harriot Stanton Blatch of illegal activity. Blatch was the leader of the Women’s Political Union and daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, first generation suffragist. Requa accuses Blatch of going above the law in bringing Pankhurst to the country.

La-Provence

When Le Provence entered New York Harbor and cleared quarantine, she was boarded by Immigration Inspector George W. Moore. Moore along with Immigration Inspector James MacGregor interviewed Mrs. Pankhurst in the first class music room. Noting her “long sealskin coat, covering an olive broadcloth suit, with a blue cloth hat,” the New York Times reported that Mrs. Pankhurst was cordial and answered that she had not been convicted of arson but had been convicted of conspiracy. After being told that she would be taken to Ellis Island to appear before the Board of Special Inquiry, she willing went along and told reporters gathered, “I have come here to tell the American people the whole story of our activities in England in the fight for suffrage.” When asked about carrying out a hunger strike she replied, “Our motto is, ‘Give us the vote or give us death.’”

On October 18, 1913, the Board of Special Inquiry, led by Inspectors Eppler, Steward, and Schell met and interviewed Pankhurst. Asked if she had ever “come in conflict with the authorities in England,” she answered simply, “Oh, yes.” They went on to ask about her arrests and the resulting prison sentences. On more than one occasion she was accused of obstructing the police when she tried to deliver petitions for women’s suffrage to British Parliament.

More damning was the allegation that her speeches encouraged violence. During one incident following one of Pankhurst’s meetings more than 60 shops were damaged with windows broken. She was sentenced to 9 months after that incident but only served 6 weeks because she became ill after going on a hunger strike.

More recently, in March 1913, followers of Pankhurst had placed explosives in the unfinished house of the British Chancellor of the Exchequor, Mr. Lloyd-George, causing significant damage. Tried for conspiracy Pankhurst pleaded not guilty, but was convicted and sentenced to three years of penal servitude. The jury recommended mercy and Pankhurst told the Board of Inquiry that her sentence had been cancelled. Nonetheless and perhaps unsurprisingly for the time, Pankhurst was held at Ellis Island for deportation.

President Woodrow Wilson was besieged by telegrams seeking Pankhurst’s release. Harriet Stanton Blatch’s telegram notes that the Women’s Political Union had been assured that Mrs. Pankhurst would be allowed to land. The telegram from the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association was signed by Katherine Houghton Hepburn (the mother of the famed actress.) A telegram from Chicago was signed by Jane Addams, noted for her pioneering social work.

During President Wilson’s first term he had been plagued by the women of the suffrage movement. Pledging support during his campaign, Wilson did an abrupt change when elected. His inauguration ceremony was marred by a demonstration by women suffragists nearby. Women began to picket the White House, some chaining themselves to the gates and many prominent women were placed in jail. Like Pankhurst, they went on hunger strikes. Perhaps it is unsurprising that President Wilson chose not to tangle with Pankhurst and she was released from Ellis Island after a 48 hour stay.

Pankhurst would go on to make speeches across the country, accompanied by American leaders of the suffrage movement including Harriet Stanton Blatch and Alice Paul. She was hosted by Mrs. O.H. Belmont – better known by her former married name, Alva Vanderbilt.

Upon Pankhurst’s successful tour she returned to England where she was promptly arrested again. She was let out again a few weeks later. Pankhurst sailed to America again in 1916, this time to campaign for the relief of the Serbians whose country was devastated by World War I. She was briefly detained at Ellis Island but again released. The United States was coming closer to being embroiled in what was known as “the Great War” and there is far less press coverage or letter writing regarding her visit.

Pankhurst’s struggles remind us what a long and difficult battle it was for women to gain the right to vote through the 19th amendment, 100 years old in 2020. It also demonstrates that Ellis Island was not only the site where countless poor immigrants were processed, but became part of the larger political landscape of its time.